How to Interpret and Use Nazi-Era Archival Files in Research

The vast body of surviving Nazi-era documents — ranging from military reports and personal diaries to Gestapo records and administrative correspondence — remains one of the most significant resources for historians. These files are central not only to understanding the workings of the Third Reich but also to preserving memory and justice. For researchers, genealogists, and students, approaching these materials critically is essential.

- Understanding What These Files Are

Archival files from the Nazi period can take many forms:

- Official records: Orders, decrees, and memoranda produced by ministries, the Wehrmacht, or the SS.

- Personal writings: Diaries, letters, and memoirs of soldiers, civilians, or political leaders.

- Intelligence and police files: Surveillance reports, denunciations, and Gestapo case records.

- Trial and post-war materials: Interrogation records, witness testimonies, and translations prepared for Allied use.

Each type has its own character — some are bureaucratic, others personal, and many are shaped by fear, propaganda, or the prospect of later accountability.

- Why These Files Matter

These documents are invaluable for:

- Historical scholarship: They provide primary evidence for understanding decision-making, ideology, and daily life under the regime.

- Legal accountability: Many were used as evidence at the Nuremberg Trials and other proceedings.

- Genealogy and memory: Families trace relatives’ roles — whether as victims, perpetrators, or bystanders — through surviving personnel files and correspondence.

- Public history: Museums, films, and literature often draw directly on these primary sources.

- Approaching Them Critically

When dealing with Nazi-era archives, a critical mindset is vital:

- Bias and propaganda: Official records often reflect the Nazi worldview and should not be taken at face value.

- Silences and omissions: Absences can be as telling as what is written — for example, euphemisms like “special treatment” masking mass murder.

- Authorial perspective: Was the file written by a loyal Nazi, a reluctant bureaucrat, a resister, or someone writing defensively after the fact?

- Translation and mediation: Many surviving files were translated by the Allies; researchers must be aware of possible interpretative layers.

- Methods for Research

Practical approaches include:

- Cross-referencing: Compare one document with others (e.g., orders against soldiers’ diaries) to identify discrepancies.

- Thematic analysis: Track themes such as antisemitism, propaganda methods, or military strategy across multiple files.

- Chronological mapping: Place documents within a timeline to understand evolving policies (e.g., escalation from persecution to extermination).

- Microhistory: Use one file (such as a Gestapo case folder) to reconstruct the lived experience of an individual or community.

- Modern Tools for Interpretation

Today’s digital environment makes working with these archives more accessible:

- Digitised collections: Many institutions (e.g., Bundesarchiv, Yad Vashem, USHMM) have placed scans online.

- Keyword search: OCR technology allows researchers to scan vast collections quickly.

- AI-assisted tools: Emerging platforms help translate, summarise, and cross-link documents across collections.

- Metadata tagging: Enables tracing individuals, places, or organisations across thousands of files.

- Ethical Responsibilities

Researching Nazi files is not only a technical exercise — it comes with ethical obligations:

- Respect for victims: These files often document persecution, suffering, and murder; they must be handled sensitively.

- Awareness of misuse: Far-right groups sometimes cherry-pick or distort archival sources; rigorous context prevents misrepresentation.

- Transparency in citation: Always note the origin, archive, and context of a document when quoting it.

- Uses Beyond Academia

Archival files from the Nazi era serve multiple audiences:

- Historians: Building scholarly arguments about the structure and crimes of the regime.

- Families: Seeking closure about the fate of relatives.

- Educators: Teaching students how to handle contested history with evidence.

- Artists & filmmakers: Bringing authenticity and nuance to cultural representations of the era.

Conclusion

Nazi-era archival files are both instruments of power and witnesses of history. Interpreting them requires a balance between rigorous critical analysis and deep ethical awareness. Used carefully, these sources help us reconstruct events, honour victims, and understand the machinery of dictatorship — ensuring that history remains anchored in evidence rather than myth.

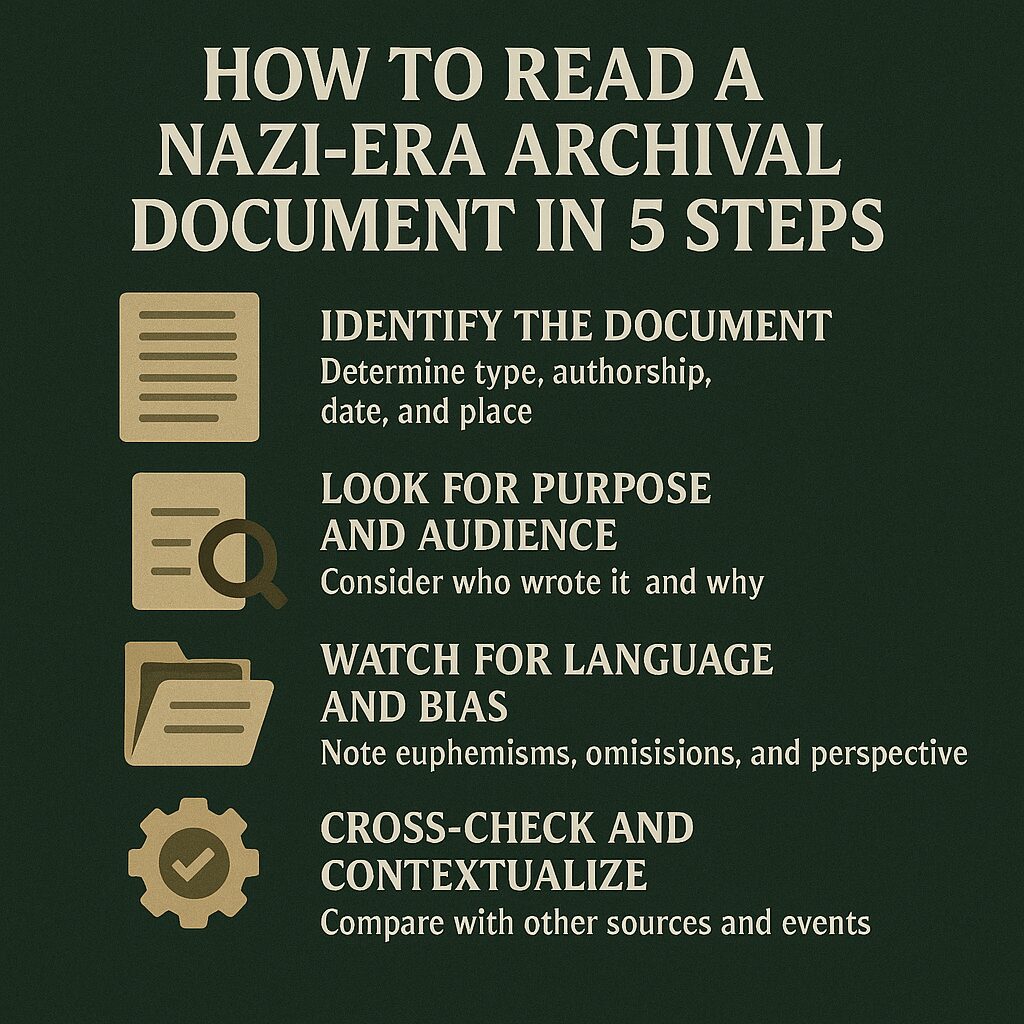

How to Read a Nazi-Era Archival Document in 5 Steps

A Practical Guide for Students and Researchers

Working with files from the Nazi period can feel overwhelming. They are often long, bureaucratic, and filled with propaganda or coded language. Here’s a simple method you can use to make sense of them.

- Identify the Document

Ask the basic questions first:

- What kind of file is it? (diary, police report, military order, propaganda leaflet, letter?)

- Who wrote it, and in what role? (a Nazi official, a soldier, a civilian, an intelligence officer?)

- When and where was it created? (context matters — 1933 is very different from 1943).

📌 Example: A Gestapo report is very different from a soldier’s personal letter.

- Look for Purpose and Audience

Every document was written for a reason. Ask:

- Was it meant to be private, or was it for official circulation?

- Was the writer recording facts, justifying actions, or persuading others?

- Who was expected to read it?

📌 Example: A diary entry might be candid, while a propaganda pamphlet was designed to convince or deceive.

- Watch for Language and Bias

Nazi files are full of euphemisms and ideological framing.

- Learn the “code words”: “special treatment” often meant execution, “resettlement” could mean deportation.

- Consider how the writer’s position (loyal Nazi vs. reluctant bureaucrat vs. victim) shaped the tone.

- Notice what is left out as much as what is included.

📌 Example: A transport list might list “departures” without saying that the destination was a death camp.

- Cross-Check and Contextualise

One file is rarely enough. Always ask:

- Does this match or contradict other documents from the same time?

- What do we know from survivor testimony, trial records, or Allied intelligence?

- How does this fit into the larger timeline of Nazi policies (1930s persecution → 1940s extermination)?

📌 Example: Compare an SS order with diaries from local residents to see how policy affected daily life.

- Reflect on Use and Responsibility

Finally, think about why and how you’re using the document.

- Are you studying policy, memory, or personal experience?

- How can you use it responsibly in your project or paper?

- Are you presenting it with enough context to avoid misinterpretation or misuse?

📌 Example: Quoting a Nazi report requires adding background so readers understand its bias and coded language.

Quick Checklist for Students

✅ Who wrote this, when, and why?

✅ What kind of document is it?

✅ What bias or coded language does it contain?

✅ How does it fit into the bigger picture?

✅ How should I present it responsibly?

By following these steps, even a single Nazi-era file becomes more than just an old piece of paper — it becomes a window into history that you can critically examine, contextualise, and use to build evidence-based understanding.